Existential and ontological difficulties

The Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project published a survey in October 2023 of over 600 people who reported post-psychedelic difficulties lasting longer than a day. We asked them to describe their difficulties then we themed them into eight broad categories and 60 sub-categories. One of the main categories of difficulty was ‘existential / ontological difficulties’ - 42% of responses fitted into that category. We also created the sub-category ‘existential struggle’, in which we put any responses that mentioned struggling with meaning and purpose after the psychedelic experience. 17% of responses fit into that sub-category, making it one of the most common forms of extended difficulty. Here’s one example:

"I entered the experience believing that my experience is the literal real external world. The experience contained me living out my worst fears, the deepest possible shame. Other experiences so bizarre and dreamlike I could not make sense of them. These memories left a legacy of confusion about what deeper model of reality to use, and repeated experiences of flipping between these models at different times."

We recently undertook a follow-up survey of 159 people who reported post-psychedelic difficulties, asking them to describe specific symptoms, how long they lasted, how severe they were, and what specifically helped with each specific symptom, to try and pick apart some of the findings of the first survey.

As part of this follow-on survey, we asked people whether they had ever experienced ‘an external sense of struggle to comes to terms with the meaning of life or the nature of existence after the psychedelic experience’. 103 people out of the total of 159 said they had experienced this difficulty. On average, they said they experienced this difficulty for around 17 months - significantly longer than respondents said they experienced other forms of post-psychedelic difficulty, like increased anxiety or social disconnection.

To dive deeper into the phenomenology of post-psychedelic existential confusion, we undertook a qualitative study of 26 people who described symptoms like it in our 2023 extended difficulties survey. Pascal Michael and I were part of the team who did interviews and then analysed transcripts for themes, and the final paper was lead-authored by Eirini Argyri of Exeter University. It’s available as a pre-print here. What is post-psychedelic existential confusion like, what might cause it, and what did people say helped them cope with it?

Contextual factors

First of all, we looked at contextual factors - what drug people took, in what context, what was their life-situation when they took the drug, what was their intention, do they know the dose and if so how high was it, and so on. We, like other researchers, are interested in what might make post-psychedelic difficulties more likely to occur.

With such a small data-set (26 people) we can’t draw conclusions, but we can see some characteristics that fit with others’ hypotheses (see Bremlah 2023) - in some cases, youth and inexperience seemed to play a role, as did a high dose or unknown dose, and a lack of social contacts with whom people felt they could discuss their experience. Respondents showed a range of motivations, from healing to curiosity (‘I wanted to blast out there’). All of them struggled to fit the experience into their existing map of reality - the trip ruptured their worldview.

The trip itself

All the experiences in our study could be defined as Ontologically Challenging Experiences (OCEs) - mystical or religious experiences which were awesome and terrifying; bewildering encounters with, or possession by, entities; feelings of being in eternal hell; or being cosmically responsible for the universe; perplexing spiritual insights or commands, and paranormal experiences that challenged participants’ physicalist conceptions of self and reality.

For example, one young man took psilocybin on his own and felt like he encountered aliens who told him the secret of the universe - yet he couldn’t quite understand what they were saying. Another interviewee felt telepathically connected to her boyfriend, an intense experience which destabilized her sense of reality. Another woman took a high dose of mushrooms on her own and felt like she encountered a demon, who she continued to feel possessed by for months afterwards.

Some reported feeling a mystical sense of oneness, ego-dissolution or unity with all things, but this was often experienced as tragic, lonely and nauseating, triggering feelings of meaningless. For example:

"I was having this really deep experience with my guide, that we were truly one person. And I was like, Oh my God, that's so depressing. Right? Like, is there no novelty in the world? Like if this is all in my head, oh, what a sad small world, right?... to realise that it's all actually happening in my head was the most depressing thing I could think of...'If this is all in my head, it’s just a dream' - it's meaningless."

"I did not experience this loss of sense of self as a positive thing at all… This was an experience of pure fear, a feeling of being cut away from everything real and alive…. I felt like this experience had kind of unzipped who I was, and instead of finding something loving or divine or sacred there, I found the exact polar opposite. I found separation and loneliness and meaninglessness, and despair and entrapment…"

People’s experiences were not characterized by ‘deeply felt positive mood’ - on the contrary they felt intense fear, overwhelm, confusion, and sometimes a feeling of what Stan Grof called ‘no exit’ experiences. “I'm just always going to be this way”, “I have done something, like, deeply irreparable to my existence.” ‘I have broken my brain’.

Extended feelings of existential confusion after the trip

These Ontologically Challenging Experiences then led to extended feelings of ontological shock and existential confusion lasting weeks, months or years (we found in another survey of over 100 people that existential confusion lasted on average 17 months). For example:

"Most days I would feel anxiety, fear, sit in disorientation and deeply saddened by my existence, which progressed into existential crisis… the questioning of this whole universe, why are we here, what's the point of this?"

Participants reported a sustained destabilisation of their sense of reality:

"The psychedelic experience was so powerful that it fundamentally challenged my perception of reality, and how well I could trust my perceptions in the day-to-day....the thing over the long term was ontological. I just wasn't 100% sure whether... I could never really — and to this day that's true — really trust my sense of what was actually going on."

Their sense of identity also sometimes felt shattered or violated by the psychedelic experience:

"My sense of self felt as if it had been chewed up and spat out by the forces at play in the realm/ reality that is when on ayahuasca. It felt delicate compared to before and a sense of an unwanted degree of loss of control gave me the sense of being broken beyond my comfort zone. As my sense of self felt so bashed around I felt quite nihlistic and apathetic. It made no sense to trust in a self as there is such an awesome and huge world beyond sole identity with self."

Many participants felt stuck in an obsessive preoccupation with making sense of the experience:

"I wanted to understand existence somehow. And I knew I couldn't... in this DMT high, you feel like you can understand more things...afterward... It seems like almost more real or [you] have a better grasp of things. And then you come back and you're like, 'that benefits nothing...what the heck'... this wanting to understand the meaning of it all or the universe or existence... and then just not being able to take no for an answer."

"I'm still trying to understand that experience... It would come up and I would talk about it with people. But it almost- just- it just didn't quite get to the nub of what the- what I was trying to express. I could never quite explain it properly."

Some participants reported coming away from their psychedelic experience with feelings of religious or spiritual disappointment when they didn’t encounter the loving God they expected:

"I went looking for God and for love and for connection and I got the exact opposite. gave me this feeling of existential betrayal that to this day, I feel has created a very, I mean, profoundly distrust for me, of a very deep sense of like not feeling safe in life."

The extended ontological shock could be particularly acute for those who encountered ‘entities’ during their psychedelic experience, or who experienced paranormal phenomena like telepathy or mind-merging. In some cases, they continued to experience these phenomena in the days, weeks or months after the experience. This challenged their western, materialist, non-animist world-view and left them deeply confused about the nature of reality, whether spirits or energies exist (as is commonly understood in the context of Amazon plant-medicine) or whether such experiences are symptoms of psychosis (as is commonly understood in the context of western psychiatry):

"I would have spirits in my room..I could hear them, and I could feel them as well. ..And what I think happened, in my case, and very possibly other people's cases, in terms of psychosis and schizophrenia, is that my sensory perception was kind of ripped open to a lot more than what is normal, and than I'm used to..And because it happened so suddenly, without being taught or without practice, it's absolutely overwhelming, and scary and terrifying."

Finally, people often receive insights, lessons, messages or even commands during psychedelic experiences, which feel utterly convincing and revelatory. These insights or messages can often be healing or encouraging. Aldous Huxley, for example, felt he encountered ‘Love as the primary and fundamental cosmic fact’ during a psychedelic experience. However, the insights or commands people receive during psychedelic experiences are not always so clear, comprehensible or encouraging. One participant, during a solo psilocybin experience, suddenly ‘knew’ that their mother had died and it was his fault (this turned out to be untrue). Another participant in a group psychedelic experience saw a message in lurid lights: ‘You are a shaman’. A third participant, a university student, took psilocybin alone and encountered what they experienced as aliens, who communicated to him the secret of the universe - he felt he understood the message but then kept on forgetting, and emerged bewildered about how to integrate the experience into his everyday life:

"Growing up in this little small town where no one talks about anything other than work and the day to day stuff…And then to have this experience… How can I engage with this world now, like, try and pretend that this degree is worth something? When there's things of much more cosmic significance that's potentially going on? And everything just seemed like…what's all this about now?"

These extended ontological and existential difficulties were accompanied by extended emotional difficulties, especially anxiety and fear.

"I was just lost and couldn't really speak. I suppose I felt shell-shocked."

"I would get panic attacks fairly regularly. for that year following the incident probably a few times a week."

Several participants also reported social difficulties, especially feelings of isolation and that no one around them would understand what they were going through:

I would have loved to have someone in my life that was on the same wavelength in terms of the stuff I've been reading, and wanting to go deeper into the experience, but there was no one around me that would even entertain that notion, so yeah, definitely it just got bottled up. This is probably the first time I've ever spoken about it or revisited it in a proper manner.

Participants also reported behavioural difficulties, especially disruption to their everyday functioning and ability to work. Almost half of the interviewees explicitly referred to their psychedelic experience as traumatic and reported symptoms of PTSD.

What helped / what didn’t help?

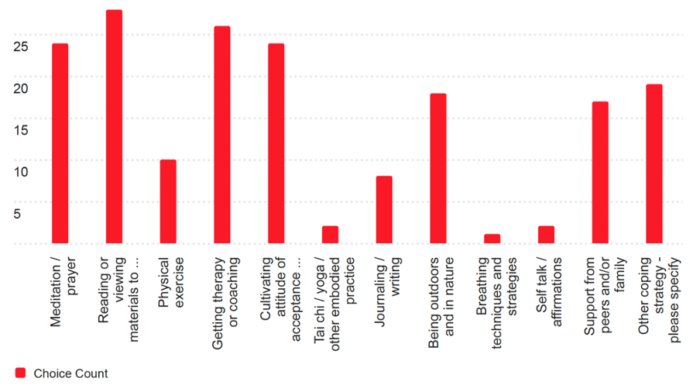

Looking at the follow-on extended difficulties survey, we can see some of the coping methods that 100 people said they found helpful with post-psychedelic existential confusion. Popular coping methods included meditation / prayer, reading useful information or books, getting therapy or support from peers, cultivating an attitude of acceptance, and being outdoors.

We also explored how people navigated the difficulties that arose from ontological shock and its accompanying existential confusion. Interviewees said they were helped by grounding, sense-making, acceptance and social reintegration.

Various practices were described as helpful because of their grounding effects. These included body work (yoga, acupuncture, massage, breathwork), experiences with water (hot baths, cold showers, swimming), spending time in nature and trauma release exercises (such as shaking and screaming).

I really started to get into… body oriented practices to ground because that was in first instance what I really needed, to ground. To be present again… just like with the sensations in my body, and, learning to recognise, if my stomach contracts, what does this mean? Just letting it be? Not thinking, Oh, my God, I feel awful and this is never going to end and then it was very cognitive again. Learning to feel into the moment, into my body again.

Grounding through embodiment practices appeared to counteract dissociative obsessive tendencies, where participants felt ‘stuck in their head’. Attention-focus practices (such as repeating mantras, nail-art, colouring, counting and certain types of meditation) were cited:

One of the things that I did was a simple countdown practice. So…when I was getting into obsessive thinking or high anxiety regarding the experience, I would count down from three…So not fighting against the desire to anxiously think or ruminate…but clearly labelling myself, this is here, but this isn't helping. Then I would redirect my attention back to my body into the present moment and just try to be with my life as it was happening in the moment.

Meditation was helpful in some cases but unhelpful in others as some described feeling ‘too open a vessel’, or felt that attempting to meditate would trigger them to re-experience their challenging altered state. It is possible that meditative introspection adds to the cognitive overload of someone dealing with ontological shock and accentuates preoccupation with sense-making. Someone dealing with such challenges may instead benefit from focussing their attention on something outside of themselves, to help them return to the present moment.

The normalisation of the ontologically shocking experience was also described in participants' accounts of what helped. This was done through both cognitive and social normalisation. Social normalisation involved speaking to others who have had psychedelic experiences and related challenges, sharing their experience with loved ones, connecting with a community that understands their experience and accepts them. The value of such interpersonal support was mentioned by almost all participants.

Just having someone say that it's just like a normal thing that happens and like kind of I remember it being really reassuring and just knowing that it was okay, that someone else had been there and had some nice advice.

I discovered a spiritual awakening sharing circle...that was literally my only support because I was going through this all alone, living alone in my flat. But every month I had this group I would go to, and for five minutes I would talk about this crazy stuff I was going through with this demon and people didn't judge me. And that was what kept me going.

Cognitive normalisation involved finding frameworks (religious, spiritual, scientific and other philosophical ideas) to understand the experience. People described going through major worldview shifts - sometimes from atheist to spiritual. One interviewee, for example, began the pandemic as an atheist dominatrix. By the end of the pandemic, after a period of intense psychedelic experimentation, she had become a trainee Buddhist nun. Another interviewee transitioned from an atheist in the US Airforce to a member of a chanelling community. But others described different worldview shifts - from esoteric to evidence-based naturalism. And sometimes people said they were helped by letting go of their need for big answers.

Another important aspect of cognitive normalization was people reframing the experience as an inner state rather than realisation of a literal external truth about reality and the universe.

What I saw on my trip was just that – the quality of my mind and how it was determining the quality of my life. The trip showed me in what direction my mind was pointed.. that helped me strip this sense of objectiveness from my experience, and allowed me to connect with the sense that what I experienced was not true objectively. It was simply true and relevant to me. And that's something that definitely helped stabilise me a lot

This is an important point so let me give two quick examples that I came across online this week. This person posted on Reddit’s r/psychonaut page describing a hellish 5-meo-DMT experience, which six years later has put them off having children.

Now, six years later, I cannot fully commit to the love of my life to have the children we've always wanted, because 5-meo has propagated a deep association between children, consciousness, suffering, and hell. My body won't let me do anything that could EVER have a REMOTE chance of furthering that hell, or letting more conscious beings end up there. There was no trace of this between the same partner and I before the trip. I was eager to have kids right away, though we waited for life logistics reasons.

Commenters gave them good advice: ‘You assume this is the ultimate truth to which you guide your life and existence? You could be wrong. Don‘t make it a religion.’

Compare that to a recent interview by Uruguayan actress Barbara Mori, who describes a series of ayahuasca sessions where she felt she was in a loveless hell.

For me, the plant was a great learning experience, and at first it really shook me up. It confronted me with the hell that was in my head , which everyone has a different one. For me, it can be a world without love. The first five ayahuasca ceremonies I did, I was in hell. I said, ‘My God, what is this? In the fifth ceremony, I felt that I was connected to the earth. It sucked out all the information I received since I was born into this world. I began to see the words 'You are worthless', 'If you stop being beautiful, your value will go away', everything that my family and society told me. Until, suddenly, it stopped and I was reborn.

Mori found the hell experience helpful because she came to see it as a projection of her inner state and her inner self-beliefs, rather than a literal revelation about divine reality.

What was not helpful

Participants noted the impact of lack of societal awareness and infrastructures to support difficult experiences following psychedelic use. A lack of broader cultural understanding of the metaphysical aspects of psychedelic experiences caused further isolation when trying to deal with a difficult psychedelic experience.

The culture isn't there to support [psychedelic experiences] yet or entertain the possibility that there might be something deeper. I’m struck by the lack of care for the spiritual in our culture, especially in Britain. We just don't have it. As a species or as communities. How to reintegrate the spiritual back into our lives.

While certain spiritual frameworks (such as spiritual emergence) helped some interviewees process their experience, in cases where spiritualist interpretations were forced by others, including retreat guides, they caused more distress, fear and anxiety:

What's so scary is that he [the guide] would pin everything to an entity possession, which was even scarier. So, instead of taking ownership of this compromised facilitation, instead of taking responsibility, he would say oh, you must have been possessed by an entity.

This also occurred when seeking advice on online forums:

I would wake up with some bruises and stuff and then I put it on Reddit and someone was telling me, oh, this is you're being abducted in the night and so that really scared me, that made me much worse... Because people were telling me things that weren't helpful. And someone else read it and commented like, Oh, you're gonna die. So that added a lot to my fear.

Obsessive escapist coping was recognised as counterproductive, whether it involved further psychedelic substance use or intellectualisation

Trying to intellectually solve the experience, trying to think my way out of it…to obsessively find a book or a talk or something. Some magical sentence about the nature of self and reality that is going to cure my anxiety… The search for the magic bullet… that is definitely not an effective strategy.

Case studies

Steve was a 22-year-old psychology student at a British university. He had previously experienced depression but had largely positive experiences with psychedelic drugs. He was attracted to psychedelic books and articles and was curious to explore altered states of consciousness:

I come from a small town…And I'm listening to this guy [Terrence McKenna] on the internet, talk about these mind blowing experiences. And I was just like… ‘Give me the keys to the universe!’. The reality that's presenting itself is so mundane. I felt like there’s gotta be more…I just want to be blasted out.

He took three grams of magic mushrooms alone in his university room one night, and experienced a bewildering encounter with alien-like entities, who explained the secret of the universe to him in a way he felt he almost understood but kept forgetting. The experience left him feeling ontologically shocked and confused about the meaning of the experience and its relation to his everyday life. He told us he felt increasingly detached from his university work and from other people, and reported feeling some derealization. He found himself obsessively thinking about the meaning of his psychedelic experience, to the detriment of his everyday functioning:

Growing up in this little small town where no one talks about anything other than work and the day to day stuff…And then to have this experience… How can I engage with this world now, like, try and pretend that this degree is worth something? When there's things of much more cosmic significance that's potentially going on? And everything just seemed like…what's all this about now?

Steve says he came to an acceptance that he would never completely understand his experience and that he needed to overcome his attraction to abstract and esoteric ideas and focus more on the here-and-now, while also strengthening his social connections.

This process of reconnection, just talking to old friends and family and making sure that [I was taking] exercise, time in nature, things that were very grounded in the earth. Also music – playing music. Yeah, I think that I could say things that would have been unhelpful, was going even further into books and abstract theories and ideas.

Nonetheless, he says: ‘that sort of existential dread still comes up occasionally to this day - maybe a year or so later.’

Beth was 24 years old when she had her first LSD trip with her partner, at a BnB. They both had a metaphysical ‘telepathic’ experience of aliens visiting them to send them an urgent message. She describes feeling the intense weight of responsibility that they had been asked to deliver an indecipherable message, which left her distressed. Her partner was also shocked after, but refused to communicate about it, avoiding discussions, and their relationship broke down. She was obsessing about the meaning of the experience, trying to find a framework to make sense of it.

Being so preoccupied by what happened I could see like, for instance, my mom and my sister like having a chat about the garden or something and I was just looking at them like I would love to be able to have a chat about the garden. I wanted to speak about something such as the garden because I was just like, couldn't focus on anything like that. It was just going round and round in my head like that.

She became paranoid and afraid of being stuck in a state of insanity

I was also slightly convinced that the CIA would come because I thought this, you know, this information is too too esoteric for me to have access to… You think like that's it - I've really done it this time, there's no going back again, like I'm gonna be crazy for ever

Sleeping became a source of distress, she describes reverting to sleeping with her mum

So my dreams were like negative, quite demonic in nature, like fire being up across my ceiling and I was just really scared to dream because I thought that astral space wasn't far off the space. I've been through there and that, you know, I was more vulnerable in that space because I didn't necessarily have this much awareness of my astral body or they might be able to... these entities might be able to get me there. So I was sleeping next to my mom, like not wanting to go to sleep.

Beth felt completely ungrounded and noted that having hot baths, doing yoga, walks, and screaming in the park helped her come back to her body. She also realised that smoking cannabis was bringing her back to the challenging altered state and decided to quit, which helped her recovery. Meditation helped her eventually but at first ‘she felt too open of a vessel to do that’.

She describes needing to create a bridge between her metaphysical altered state experiences and normal everyday life, which was her process of integration

And then being able to for instance, have those conversations about car insurance and, and still know that I've had this experience… learning to deal with that side of things… going from the mystical to the mundane and learning to bridge that gap and the disparity between them and not feel like you're betraying either one side but as you've done two things coexisting and being better for it, like both of them being individually better, because of the other one, I think that's what I realised and, yeah, that's what I would say is my definition of integration.

Encountering the framing of spiritual emergency helped her reframe her experience and gain confidence

I read about spiritual emergency and realised you know, there is a way out of this. You think like that's it - I've really done it this time, there's no going back again, like I'm gonna be crazy for ever. So hearing that narrative that that wasn't the case was just lifesaving itself. I understood the significance of what I was going through as something that could be overcome.

Kirsty was 43 years old when she had 33g of truffles at a guided group psilocybin retreat in the Netherlands. She was feeling isolated during the pandemic and hoped the trip would help give her clarity to make life decisions. Her psychedelic trip experience was positive and she describes being able to ‘really let go’. She encountered dead relatives in the form of trees, but in the aftermath she struggled, becoming increasingly preoccupied with mortality and making sense of her experience.

So I remember going on a long walk with [a friend] after I got back and telling her about some of my challenges … telling her I feel like I need to make sense of it all but I can't. It's things like feeling like someone who dies can go and become a tree…

Like others she found reassurance in advice not to take her experience literally but she did not feel that was always possible

[her friend and] the facilitator of the trip, made it clear ‘what you experienced, you should not necessarily, you shouldn't interpret it as literal. It was an experience in your mind’. It's like a mystical experience. You can't necessarily make sense of it… I think that's helpful but also felt like something I didn't totally have control over.

She also describes feeling frustrated about the contrast of the feelings within the experience and the anxiety she was left with after.

And I was frustrated too because during the trip I felt so connected to love and like very grateful for all the support I do have in my life and I feel like in the anxiety I've been forgetting about all those good parts of the trip like I was really honing in on some of the more existential stuff that came out and really going into like the catastrophizing of it as opposed to kind of keeping a more rational point of view on it.

Like many others, Kirsty found that sharing her experience with others helped her in her recovery

I talked to friends about it. And I kind of found some relief in talking to friends, like other people that had similar experiences, so I knew I wasn't alone in that.

On entity encounters

It is quite common to encounter ‘entities’ – what other cultures would call spirits, angels or demons – while on psychedelics. A 2015 survey of 800 psychonauts by Fountonglou and Freimoser found that 46% of ayahuasca-takers reported ‘encounters with suprahuman or spiritual entities’, as well as 36% of DMT-takers, 17% of LSD takers, and 12% of psilocybin-takers. Similar percentages reported ‘experiences of other universes and encounters with their inhabitants.’

This sort of entity-encounter is typically a positive experience, but not always. In a Johns Hopkins survey by Davis et al in 2020, 2561 people said they encountered entities while under the influence of DMT. They usually described these entities as a guide or helper, but 11% described the entity as a ‘demon’, ‘devil’ or ‘monster. For 78% of people, the entities were experienced as ‘benevolent’ or ‘sacred’, but 16% felt they were ‘negatively judgemental’ and 11% felt they were ‘malicious’.

Whether positive or negative, entity encounters can upend a person’s worldview. Most respondents (72%) in the Johns Hopkins survey thought the entity continued to exist after their encounter, and 80% said that the experience altered their fundamental conception of reality. The number of respondents who identified as atheist fell from 28% before the encounter to 10% after.

Encounters with both positive and negative entities are particularly common on ayahuasca. In Bouso et al’s 2022 paper on adverse ayahuasca events, which used data from the 11,000-respondent Global Ayahuasca Survey, 14.9% reported feeling ‘energetically attacked or a harmful connection to the spirit world’ (of course, an energetic attack could be experienced as coming from another human). Such experiences may be particularly common in ayahuasca experiences because of the setting of shamanic culture. One reader tells me: ‘I think shamans plant this idea with you when you arrive [in the Amazon']. Then they can help you and expel your demons and you feel satisfied.’

In a survey we did of 129 people who work in the psychedelic industry (as guides, researchers, facilitators, coaches etc), 72% said they believed in the existence of entities - good or bad - which can be encountered on or off psychedelic drugs. This belief is particularly common among practitioners of Internal Family Systems (IFS), who refer to negative entities as 'unattached burdens'.

The beliefs of facilitators can be implanted in clients on psychedelics or off them, so if you're at a retreat or in a therapy session and the therapist or facilitator tell you something like 'you have an entity within you', you might come to believe this - it doesn't mean it's necessarily true, nor is it always helpful.

The question of how to deal with such entities (real or imagined, benign or malevolent) is an issue at the blurred boundary between psychotherapy and theology. The most common attitude – taught by veteran Johns Hopkins psychedelic guide Bill Richards, Timothy Leary and others – is that if monsters arise during the psychedelic experience, you should and transform them. Bill has said:

‘In and through, in and through’ is the mantra. If an inner dragon, boogeyman, or monster should reveal itself then we go right straight towards it as rapidly as possible and say, ‘Well, hello. Aren’t you big and scary! What can I learn from you?’ And so instead of running away and getting into panic and paranoia and confusion and even perhaps needing to go to a psychiatric emergency room, you look it straight in the eye and say, ‘Boy, you’re an ugly part of me but what are you made of?’And when you go towards it, inevitably there’s insight…I always say what devils hate most is being embraced.

This is of course a Jungian attitude - you should recognize and accept your ‘shadow’ when it arises. It’s also an attitude one finds in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which has been an influential text for psychedelic science ever since Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert made it the basis of their 1964 Psychedelic Experience Manual. In Tibetan Buddhist theology, any monsters, demons or wrathful deities you encounter now or in in the afterlife should be recognized as aspects of consciousness, real at the conditioned level (and perhaps deserving of compassion as suffering sentient beings) but empty-of-self at the ultimate level, and transformable through insight.

However, other traditions might see positive or negative entities as real aspects of the spirit world which can attach to the self in positive or negative ways. Shamanic and neo-shamanic cultures have this view, as does Internal Family Systems and some other alternative forms of psychotherapy. They teach that such negative entity experiences sometimes require exorcism.

It's impossible to scientifically test such theories, and there's not even any evidence on how many people find such procedures helpful or harmful. However, we can say that the idea of spirit possession and exorcism, while common in non-western cultures, is completely alien to western culture. It's also a theory of illness and healing which hands a lot of power to the 'expert' doing the exorcism, while taking that power from the individual who is supposedly possessed.

At CPEP, we are agnostic about whether such entities really exist, for good or bad. Either way, it seems like whether you can something a negative entity or a mental disorder, similar things can help to heal the person: social support, focus on healing, not giving the disorder / entity too much of your attention or energy, cultivating positive emotions, finding coping techniques that help you ground in the present and in your body, finding things that give you back your enjoyment of life.

You can read more about negative entity encounters here.

Further resources

For further information and support, the following web resources and support services are recommended:

- CPEP runs a free monthly online support group for people experiencing post-psychedelic difficulties on the last Sunday of every month.

- Psychedelic Clinic in Berlin: Clinic at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin offering immediate support. Click here to get in touch.

- Psychedelic Support: Connect with a mental healthcare provider trained in psychedelic integration therapy and find community groups that can provide support.

- Fireside Project: The Psychedelic Support Line provides emotional support during and after psychedelic experiences.

- Institute of Psychedelic Therapy: The Institute for Psychedelic Therapy offers a register of integration therapists.

More information on existential difficulties after psychedelics:

Here is our paper on post-psychedelic existential confusion and ontological shock, lead authored by Eirini Argyri.

Below is Eirini presenting the paper at Horizons 2024.