Anxiety (including PTSD)

In the aftermath of psychedelic experiences, it is not uncommon for individuals to grapple with various forms of anxiety. Reports from surveys and personal accounts indicate that anxiety and fear are among the most common extended difficulties encountered by psychedelic users. These manifestations of anxiety may take various forms, including generalised anxiety, paranoia, panic attacks, and social anxiety.

Some of these anxiety symptoms may well be a trauma response to a highly-challenging psychedelic experience. People can sometimes be diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) after a 'bad trip'. Or they can feel flooded by previous trauma that resurfaces during a trip.

Anxiety, panic attacks, fear and paranoia most often continue for 0-6 months after a psychedelic experience before passing, and may sometimes last for a few days only. Sometimes it can last longer, in which case the person may benefit from therapy or other professional assistance.

If you're experiencing post-psychedelic anxiety, you're not alone. Many others have experienced this, sometimes severely, and the symptoms eventually pass, allowing them to enjoy life once again.

Generalised Anxiety

Many individuals describe dealing with feelings of intense fear and anxiety that persist over extended periods. This generalised anxiety can become overwhelming, even leading to physical symptoms such as trembling and shaking. The fear may not be tied to any specific threat but instead permeates daily life, casting a shadow over and affecting normal activities.

“For about 18 months, I awoke with the sun every morning full of a feeling of absolute terror…Sometimes my anxiety would be so high in the morning that I would physically shake from the energy.”

Paranoia and Panic Attacks

Some individuals experience heightened levels of paranoia, feeling a sense of pervasive threat or danger in their surroundings. Panic attacks, characterised by sudden and intense bouts of fear or discomfort, can also occur which further increase feelings of anxiety and distress.

Social Anxiety and Phobias

For some, psychedelic experiences may amplify pre-existing social anxiety or lead to the development of new phobias. Fear of being alone with one's thoughts, agoraphobia (a fear of being in situations where escape seems difficult or where help would not be available if things go wrong), and fear of permanent damage are reported by psychedelic users. These anxieties can manifest as avoidance behaviours or difficulty engaging in social situations.

Specific Fears of Psychedelic Users

There are range of specific fears reported by psychedelic users, including the fear of the psychedelic experience repeating, fear of losing control or going mad, fear of being alone’ (often because people are afraid to be alone with their mind), fear of dying (especially common if the individual felt they were dying during the trip), fear of permanent damage and feeling vulnerable or unsafe in their own mind after the trip.

“I believe the experience contributed to my general anxiety for a time, as I became aware that my psyche was not necessarily a ’safe’ place to exist within, and possibly played a role in my fear of being alone, which I suffered with around that time of my life.”

Coping strategies

Anxiety is not a one-size-fits-all experience. It can manifest in various forms, each with its own set of challenges and requiring personalised coping practices. Approaches that can help manage anxiety include educating oneself about anxiety, practicing mindfulness, using relaxation techniques, and learning proper breathing techniques.

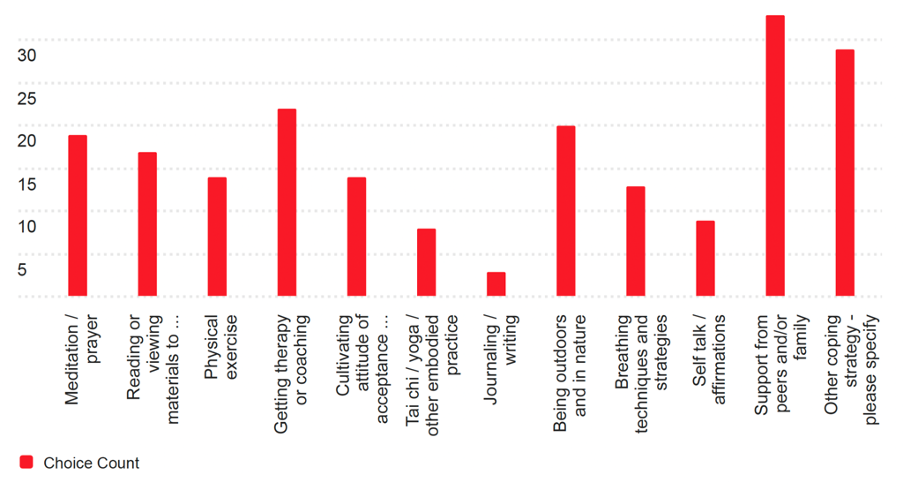

Individuals dealing with anxiety, panic attacks and/or fear found getting support from peers and/or family, therapy or coaching and being outdoors and in nature particularly helpful. For paranoia, self-education, getting therapy or coaching and meditation/prayer were reported most commonly as helpful coping strategies.

Here are some practices people generally have reported to find helpful to cope with challenging psychedelic experiences:

- Speaking to friends and family or attending a peer support group

- Speaking to a therapist, especially one who is familiar with psychedelic difficulties (CBT is often effective for anxiety and panic problems, although some also say they are helped by somatic therapy exercises that help regulate their nervous system).

- Cognitive practices like compassionate self-talk, cognitive distancing, and especially meditation and prayer

- Embodied self-care practices like exercise, yoga, walking in nature or body relaxation

- Finding useful information online and in books (e.g. the work of Stanislav Grof’s or “Breaking Open: Finding a Way Through Spiritual Emergency” by Jules Evans and Tim Read)

- Journaling

- Engage in creative activities like writing, art-making, or music

- Some people find medication helpful. Additionally, although controversial and risky, some may find that a subsequent altered state experience can help resolve their difficulties. However, this method carries obvious risks and should be approached with caution.

It is essential to explore and integrate these strategies in a way that resonates with personal preferences and needs, seeking support from professionals or trusted sources as needed.

Julie's story

Julie, a 60-year-old mental health counselor from Idaho, became interested in psychedelics as potential interventions for trauma, anxiety, and depression. She decided to explore Ayahuasca after trying mushrooms and MDMA in therapeutic contexts. Julie and her husband Jeff attended an ayahuasca retreat in Peru. The first two ceremonies were manageable though intense, but during the final ceremony, she experienced overwhelming physical and emotional trauma. Julie described the sensation as being “at the mercy of this energy,” saying:

It was just like bolts of energy or electricity convulsing through my body, and I just laid there… My body did not feel like a safe place.

The overall experience left her shaken and, on the plane home, she experienced her first panic attack. Upon returning home, the challenges got worse. She struggled with anxiety, panic attacks, and a severe loss of appetite, resulting in rapid weight loss. She recounted:

I just had such a hard time eating. I went from what was closer to 120 [pounds] in a matter of, I think, a couple of weeks, down to 104… Eating became a chore, and that was really hard because that’s one of the pleasures of life.

The physical symptoms were compounded by relentless anxiety, which she described as unlike anything she had experienced before:

It was traumatic and very overwhelming. I felt hostage… It was paralyzing, and my body suddenly was no longer safe.

Her mornings were particularly difficult:

I would wake up, and my husband would hold me or rock me… I just felt like I had lost a part of myself.

Julie also experienced intrusive thoughts that felt reminiscent of her childhood fears growing up in a strict Mormon community with alcoholic parents: ‘It activated a part of myself that was just based on fear and anxiety.’

Her coping mechanisms, including yoga and meditation—tools she had previously taught—felt inaccessible during this acute crisis. This disconnect brought an additional layer of shame: ‘I was teaching an eight-week meditation course on campus… but practicing it myself was really hard.’

Julie sought help from various sources, including counselors, integration therapists, psychiatrists, and even shamans. Unfortunately, many encounters were disappointing. Some therapists shamed her for using medications like Ativan or dismissed her trauma as her own failure to “surrender” to the experience. She recalled one healer telling her: ‘You need to get straight with your God, and you’re getting in your own way.’

This lack of understanding left Julie feeling isolated and unsupported. She also experienced social withdrawal, further exacerbating her sense of isolation: ‘I couldn’t tolerate social stuff, and my world got so small.’

Her husband, Jeff, became her primary support system, helping her regain some sense of stability. He described the difficulty of witnessing her suffering: ‘There were so many days when it was just minute by minute… I was really worried. I didn’t know if she was going to live.’

Julie's Path to Recovery

Julie’s recovery was slow and nonlinear. She found some relief in small lifestyle changes, such as taking cold showers, maintaining physical activities like skiing and running, and trying different medications. Over time, her sleep and weight began to stabilize. She eventually started Lexapro for depression, which helped her regain emotional balance:

By July, I started on Lexapro… It helped me stop crying and manage the morning anxiety.

Despite her progress, Julie remained cautious about anxiety and its triggers:

I’ve had to befriend certain things again, like anxiety being a normal part of life, but I never want to go back to that place.

She emphasized the importance of having supportive people around her, saying:

You have to find one or two people that you can connect with and who can reassure you that you’re okay.

She says staying in her job, despite finding it very hard, was crucial – it gave her a schedule and stopped her world shrinking too much. She was also helped a lot by finding similar stories of people who had gone through such crises and emerged the other side, and by the support of a counsellor, and above all by her husband Jeff. They both say this was the hardest experience they ever went through (including having lost a baby).

Julie’s story underscores the need for greater transparency and preparation in the psychedelic industry. She reflected on the lack of adequate warnings and aftercare from the retreat center, saying:

It’s not necessarily over when it’s over… We’re dabbling in something we don’t completely understand.

She also criticizes the culture of shaming those who experience difficulties:

There’s this pressure to do it again, to face your fear, but that’s not the whole story. It can just be traumatic in and of itself.

Her advice to those struggling with post-psychedelic difficulties is simple: ‘You’re not alone… You are going to get better. The hard thing is the unpredictability of it.’

Further resources

For further information and support, the following web resources and support services are recommended:

- We run a free monthly online support group for people experiencing post-psychedelic difficulties.

- Psychedelic Clinic in Berlin: Clinic at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin offering immediate support. Click here to get in touch.

- Psychedelic Support: Connect with a mental healthcare provider trained in psychedelic integration therapy and find community groups that can provide support.

- Fireside Project: The Psychedelic Support Line provides emotional support during and after psychedelic experiences.

- Institute of Psychedelic Therapy: The Institute for Psychedelic Therapy offers a register of integration therapists.